|

|

HEPAP Confronts Funding Crunch by Judy Jackson

Like a spring that can be stretched only so far and still bounce back, the U.S. High Energy Physics program has reached the limit of budget stretching before irrevocable changes threaten its capacity for world-leading science. That was the message that members of the Department of Energy's High Energy Physics Advisory Panel heard from speaker after speaker at HEPAP's spring meeting, held at Fermilab on March 9 and 10.

Paradoxically, at a time when long-straitened budgets for basic science in the United States are facing the best funding prospects in many years, the budgets for high-energy physics laboratories, already eroded by a decade of inflationary effects, took a downturn in the President's Budget Request for Fiscal Year 2001. The situation is particularly troubling, DOE and laboratory officials told the panel, because both Fermilab and SLAC are poised to begin using brand-new, multimillion-dollar facilities to carry out physics experiments whose potential for discovery is unsurpassed in the world.

"We have a fifty million dollar problem," said DOE's John O'Fallon, director of the Division of High Energy Physics. "In FY2001, Fermilab has a $33 million problem and SLAC has a $15 million problem. Now, we have to fix it."

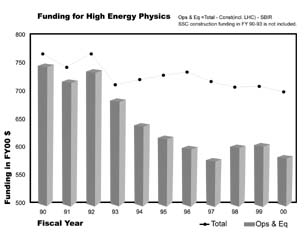

O'Fallon, Fermilab Director Michael Witherell and SLAC Director Jonathan Dorfan all showed HEPAP members the same graphic illustration of the course of high-energy physics funding over the past decade.

The chart, which appears at right, shows a $180 million decline in annual funding for operations and equipment for high-energy physics at DOE from 1990 until the present year, using current-year dollars and totals supplied by DOE's Division of High-Energy Physics. These are the funds required to utilize the investment in physics facilities. Fermilab's Witherell explained that the inflation index used to calculate yearly levels almost certainly underestimates the real inflation rate that high-tech organizations have typically faced in recent years. The "Operations and Equipment" line results from subtracting construction funds, including funding for the U.S. contribution to the Large Hadron Collider at CERN, from the total. The low level of construction funding in the years 1990-1993 occurred because the construction funding for the Superconducting Super Collider laboratory, now terminated, is not included in the total.

Witherell listed the central questions confronting particle physics in the year 2000: the search for a Standard Model Higgs boson, the search for evidence of supersymmetry, the question of neutrino mass, the investigation of matter-antimatter asymmetry, and the possibility of new and unexpected discoveries.

"The Fermilab program is addressing all of these important issues with experiments that are the best, or among the best, in the world." Witherell said. "The best chance for a discovery in the period 2001-2006 that would change the direction of particle physics is at Fermilab."

Witherell described six major construction projects now underway at the laboratory: the CDF and DZero upgrade projects for Collider Run II at the Tevatron; the NuMI/MINOS and MiniBooNE projects to study neutrino mass; the U.S./LHC accelerator effort, centered at Fermilab; and the U.S./CMS project, also based at Fermilab, to build the nation's contribution to the Compact Muon Solenoid, a major LHC particle detector. In addition, Witherell cited ongoing work on accelerator upgrades to increase the Tevatron's luminosity and Fermilab's continuing involvement in astrophysics experiments. He described critical R&D on accelerators for the future of particle physics.

"We need to protect the resources needed for this accelerator research," he said.

The Fermilab director reaffirmed the laboratory's commitment to begin Collider Run II at the Tevatron in March, 2001, and described the steps he has taken to ensure that the schedule will be met.

Witherell described progress on the NuMI/MINOS project, which will send a high-intensity beam of neutrinos from Fermilab's Main Injector to a particle detector in northern Minnesota to search for evidence of oscillation from one neutrino flavor to another. He said the neutrino experiment was "the most sensitive" to the impact of proposed FY2001 funding cuts, and that the resulting delay "would significantly reduce the impact of the experiments."

SLAC's Dorfan told panel members of the excellent performance of the laboratory's new B Factory and BaBar detector, whose current physics run began in mid-January, 2000, and will continue through August. He said SLAC has set an ambitious luminosity goal of 12 inverse femtobarns, to break new ground in the understanding of the matter-antimatter asymmetry known as CP violation.

"The B Factory is running very nicely," Dorfan said. "We'd like the machine to run like this all the time. The BaBar detector is running at over 90 percent efficiency."

Dorfan also shared the good news of NASA's announcement on February 25 that the space agency had selected the SLAC proposal for GLAST, the Gamma Ray Large Area Space Telescope. The project is a joint DOE/NASA effort for a space-based detector, to be launched in 2005. It will use technology developed for high-energy physics experiments to explore the physics of gamma ray bursts and many other aspects of forefront cosmology and astrophysics.

Funding Crisis Ahead

"If we don't improve the budget for FY2001," he said, "something will be irrevocably reset in this field. You don't recover from something like this in a year. Congress funded the B Factory at SLAC and the Main Injector at Fermilab. They did their job. And we did our job: we built them on time and on budget. Now we are ready to use them. Congress doesn't want to throw that away."

Witherell gave a similar view from Fermilab.

"We have successfully completed accelerator upgrade projects that renewed our research program without a very large new accelerator facility," he said. "We are now trying to take advantage of the scientific opportunities made available by the new accelerator complexes, but the funding level is not sufficient to do that."

Between a 20 percent cut in the base budget for the laboratories since 1992 and a five-plus percent inflation rate, driven by rising salaries for valuable scientific and technical staff, the laboratories are in real trouble, Witherell said.

"The staffs are too thin to operate the facilities, build the experiments and prepare for the future. Scheduled projects are not getting the funding they need to stay on schedule. The funding at SLAC is bad. The budget at Fermilab is even worse, worse than at any time in memory," he said.

Witherell showed HEPAP members a table, shown above, comparing science funding across federal agencies from FY93 to FY00, using numbers from the FY2001 Budget Request.

"If you're looking for a policy, this is the level at which policy is being made," he said. However, he expressed measured optimism that the final FY2001 budget passed by Congress for high-energy physics would show some improvement and said that Fermilab would develop plans for "all budget scenarios."

"These are extraordinary circumstances," Gilman said. "Years of flat-flat [not inflation-adjusted] budgets have come home to roost just as we turn on the Main Injector and the B Factory." "Is there a way to look at the process to see where we have failed?" asked University of Chicago physicist Mel Schochet. As one way to address the overall funding challenge, DOE's Peter Rosen, Associate Director for High Energy and Nuclear Physics, requested that HEPAP review the 1997 Gilman Subpanel "Report on the Future of High-Energy Physics" and provide updated interim guidance on the direction of the field. "Some think that the high-energy physics community has no clear idea where it's going," Rosen said. "We must formulate a national plan, with expenditures, timelines and road maps for the three proposed new facilities at the energy frontier and for the muon storage ring at the intensity frontier. This is an important step in developing an adequate budget." Rosen requested a brief white paper, complete by the fall meeting, outlining the steps to move ahead on the most realistic of the proposed new facilities and explaining how to unite the community in support of it. He said that time did not allow for a new full-scale HEPAP subpanel report before a planned national workshop on future options in 2001. Gilman agreed that HEPAP would prepare the white paper. Presentations on Fermilab science, the Large Hadron Collider, U.S. support for computing for LHC experiments, international science collaboration, and R&D for proposed future facilities reinforced the theme of outstanding science now underway or in prospect, with resources not adequate to achieve the benefits. Witherell's summary distilled the case for Fermilab, but he could have been speaking for all of high-energy physics. "We have great opportunities for discoveries ahead," he said. "We are exploring how to build the next generation of accelerators in an affordable way. But the FY2001 budget request would make it impossible to reap the physics reward of the Main Injector or build for the future. The FY2001 budget will set the course of Fermilab's future for many years to come." |

| last modified 3/24/2000 email Fermilab |

FRLsDFx9eyfrPXgV

"It is clear to everybody that we are committed to meet the March 1, 2001 date," Witherell said. "In Run II, we will deliver as much integrated luminosity as possible, with the assumption that LHC experiments will begin publishing results in 2006. Run II will be the longest period of pure collider running in the history of Fermilab."

"It is clear to everybody that we are committed to meet the March 1, 2001 date," Witherell said. "In Run II, we will deliver as much integrated luminosity as possible, with the assumption that LHC experiments will begin publishing results in 2006. Run II will be the longest period of pure collider running in the history of Fermilab."