|

|

Dial 1-630-CABLE ME by Mike Perricone Dervin Allen and his group of cable installers are just the folks you'd like to be able to call to wire up that new combination telephone/computer/satellite dish/home entertainment center. But they have a few thousand other things keeping them busy.

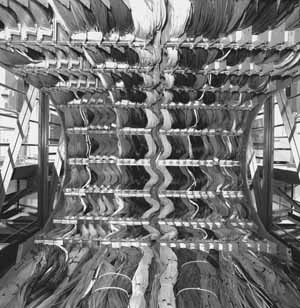

"These are the veins and the arteries," said Allen, who came to the lab in 1983 to build magnets, then joined CDF in 1984 and took part in some of the detector's original wiring installation. Much of the cable is run through a structure called the cable mover, designed to move as a component along with the 5,500-ton detector when it moves to and from the collision hall. The cable funnels into the cable mover, then fans out to connect with the individual components. Although Allen is the cabling group's only veteran from CDF's origins, most of the members have worked at the lab for a decade or more. "The group was assembled from other parts of the lab, and we've been together about five years," Allen said. "Having experience around the lab has helped a lot. They've done a great job with great teamwork. This is a very painstaking and time-consuming job." Bob Kephart, co-project manager for the CDF upgrade, noted the degree of difficulty in assembling many different kinds of cable and optical fiber, with specifications from many different experimental groups; in placing the cable across a detector with a complicated geometry and many moving parts; and doing it in a hurry. "Dervin did an excellent job," Kephart said. "He formed a very effective group from a diverse collection of technicians, gathered from all over the Particle Physics Division and from term and temporary hires. They worked as much as 20 hours a day for many months to get everything done on time." Allen estimated that Run II requires at least 30 percent more cabling than did Run I. Consider that just one component of the upgrade, the Level One Trigger, involved the placing of some 1,700 wires, with a specific destination for each end, with each wire labeled as to its function and location, and with all that information entered into a database with records for 38,808 cables that have existed throughout the history of CDF. Even if a wire is removed from the detector, its tale remains in database. "We'll enter comments, for example that a specific cable has been removed," Allen explained. "But someone looking in the database can find a cable that they remember from 15 years ago. They may find that the cable was removed on a certain date and no longer exists, but it was there at one time." Virtually all the cable used in Run I was stripped from the detector, though some has been recycled for Run II. Especially valuable is a distinctive flat signal cable, made of 50 equally spaced individual copper wires. Fast and reliable, the cable is no longer being produced, necessitating the recycling. "It's a very stiff cable, not at all user-friendly when it comes to being installed," said Allen. "We can't have twists and turns." Stiff cable is a distinctive challenge, because all the wiring must be installed with a uniformly smooth sine curve to instill a "memory" for movement. Since the big detector is designed to move to and from the collision hall, and since individual components must be accessible, the cables have to move in predictable ways and return to their original configuration. They must be well "dressed." Otherwise, it's cable chaos.

The procedure from start to finish must be equally orderly. Individual groups within the detector (for example, the Central Outer Tracker) decide what's necessary for their individual and uniquely designed chambers. They e-mail a job request to Allen, who enters the information into the cable database. Labels and spreadsheets are printed from the database, detailing a cable's function and the geographic locations for each end by area, crate and individual card and slot. Labels are affixed to the cables, spelling out its functions and geographic locations for both ends. In pulling in the cable, the crews are split to work backward from each end, dressing the cable toward its midpoint to produce even lengths and prevent any confusing excess. Then the ends are attached to the correct destination. The detector's commissioning run will show any needed modifications. Allen's schedule is constantly full. He works two nights a week in the Information Technology department at nearby Waubonsie College, coaches his son's Little League baseball team, and is a dedicated gardener. Allen's wife, Linda, is a networking architect for voice and data systems at R.R. Donnelley. They and children Natalie, 7 and Brandy, 11, recently vacationed in Alaska, viewing glaciers and the great mountain, Denali, and cruising the Inside Passage. "The glaciers are unbelievably beautiful, and two glaciers side by side can be completely different because of the terrain beneath," Allen said. Allen was especially pleased that the cruise offered "seven days without the phone ringing," but all of CDF was happy to have him back on call and keeping things connected. "We've been fortunate to have a person of Dervin's skill and dedication in charge of this important job," said Cathy Newman-Holmes, co-project manager of the upgrade. "It doesn't matter how good the detector is or how good the data acquisition system is. If they're not connected together properly, they are useless." |

| last modified 10/6/2000 email Fermilab |

FRLsDFx9eyfrPXgV

This group of Fermilab veterans has just put the finishing touches on some 800 miles of precisely placed, meticulously identified, tenderly shaped and obsessively catalogued cabling that will carry the lifeblood of electronic information to and from the revamped CDF detector in Run II of the Tevatron.

This group of Fermilab veterans has just put the finishing touches on some 800 miles of precisely placed, meticulously identified, tenderly shaped and obsessively catalogued cabling that will carry the lifeblood of electronic information to and from the revamped CDF detector in Run II of the Tevatron.

"Putting the cables in nice and neat, bundling them, mounting them on brackets, putting in the proper sine wave, all are part of what we call dressing," Allen explained. "With the amount of cable we have on the first and second floors, from the control room and the counting rooms, we'd run out of space if we didn't install it neatly dressed."

"Putting the cables in nice and neat, bundling them, mounting them on brackets, putting in the proper sine wave, all are part of what we call dressing," Allen explained. "With the amount of cable we have on the first and second floors, from the control room and the counting rooms, we'd run out of space if we didn't install it neatly dressed."