|

|

It's Beginning to Look a Lot Like Run II by Judy Jackson

Like Christmas, Collider Run II sometimes seemed that it would never come. Now, suddenly, it's almost here, with a million things left to do and a dwindling number of shopping days to pull everything together. The elves at those giant toylands, CDF and DZero, have never been busier, as they prepare for the magical day when Santa Tevatron begins sending sackfuls of high-energy particle collisions to all the good boys and girls at Fermilab's collider detector experiments. Visions of fermions dance in their heads.

True, Christmas at the Tevatron will come in March 2001, and not in December; but the good news is it looks as if everyone will be home for the holidays. Both the CDF and DZero collaborations reported last week that they'll be rolling into the beamline on time. After five years and $200 million dollars devoted to complete makeovers for both detectors, that was news worth celebrating.

In fact, CDF has already had a sneak peak at the presents. A "commissioning run" last month left collaborators beaming, verging on euphoric at the early indications of their detector's performance. Only slightly less elated were the accelerator teams who delivered billions of high-energy proton-antiproton collisions from the Tevatron accelerator they had re-awakened to duty after a long hibernation. In fact, CDF rolled out of the beamline and back into the assembly hall on November 7 with 12 million "good" events, or particle interactions, including one "poster child" event, under its belt.

"It worked," said CDF cospokesman Franco Bedeschi. "The commissioning run was very successful. It set us up for taking data. We are on schedule for the full detector to roll in on March 1. There are a few concerns. There are still a few problems. But all the detector components are ready. The detector will operate fine. The silicon will all be ready. Some electronics may still need a little work, but they will all be minor components, not critical. They will be little things that won't slow us down in any way."

Both Bedeschi and fellow CDF cospokesman Al Goshaw credit the commissioning run with focusing their collaboration's efforts.

"The intensity of activity in the commissioning run was amazing," Goshaw said. "We had to make the detector work in record time. We had a deadline. Franco and I were worried that it wouldn't happen. We wrote to the director, asking for consideration of an extension. Then, in the last ten days, the accelerator came through marvelously. We were right on the edge of our seats."

Indeed, for the first few weeks, it looked as if the run might end with a whimper. Problems with Tevatron magnets and other components kept the accelerator from delivering the collisions that CDF was breathlessly awaiting. Then, days before the run was due to end, it all came together. Suddenly, CDF had all the collisions they had dreamed of.

"Everything jelled," said Mike Church, of the Beams Division. "To get the collider going for a new run, there are just a lot of things to do. There was no single show stopper, just a lot of things that had to work."

Operations Chief Bob Mau cited an additional critical factor in attaining the requisite level of Tevatron performance.

"We had a hell of a lot of luck," Mau said.

Across the ring at the DZero collaboration, excitement mounted as the myriad components of their phenomenally complex and massive detector at last came together.

"All the pieces of the detector are now here," said DZero cospokesman Harry Weerts. "Only the second half of the silicon detector has yet to come in. We are hooking up the first half of the silicon. The other half will arrive in mid-December."

"That works out to about three hundred and fifty thousand dollars a pound for the silicon detector," Weerts said. "We were trying not to drop it."

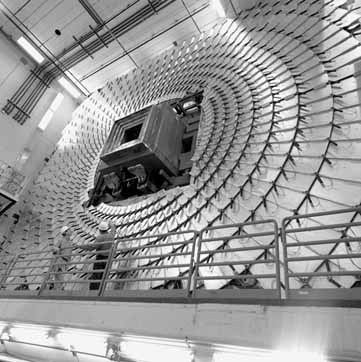

Indeed, both the huge scale of a modern particle detector and its intricate complexity, down to the last detail, are strikingly apparent as DZero puts the millions of components, large and small, together.

"There is an enormous amount of engineering in every piece of the detector," said Jon Kotcher, associate project manager. "It is a huge machine. The astonishing thing is the contrast between the detector's massiveness and its precision. And it is a complete revamp of concept and execution from the detector we used in Run I. It's all new. It's tight, much tighter than before. Everything has to nest very, very precisely together."

As the nesting proceeds, the alignment of every piece and every step must be checked and re-checked.

"Surveying is a constant job while the detector is being fitted together," Kotcher said. "Not only the pieces are a tight fit, but scheduling is a tight fit. You can't proceed with the next job until the last job is finished and surveyed, adjusted and re-surveyed."

No detail is too small to overlook. For example, in Run II, DZero will operate for the first time with a central solenoid magnet. The magnet's presence means that any tiny ferrous metal scrap or minuscule screw accidentally overlooked and left lying inside the detector would be sucked right through that expensive new silicon when the magnet turns on. Needless to say, housekeeping standards are strict at DZero these days. Martha Stewart would be proud.

In December, DZero will begin a commissioning stint of its own. However, the collisions for this round will be furnished by Mother Nature, and not by the Fermilab Beams Division. DZero will use the high-energy particle collisions created by cosmic rays streaming to earth from space to put their detector through its paces as they bring it from a dazzling collection of parts to a functioning experiment.

"There will be a mechanically complete DZero detector by March 1," Weerts said. "It will probably not have all the channels instrumented, but all the parts will be there. Some of the electronics will be late, but it will be a functioning detector. DZero will go in about the same stage where CDF went into its commissioning run."

With the end of their endless makeovers now in sight, both collaborations can now begin to focus on the point of all their efforts, the physics of Run II. Both teams have begun the transition from construction project to operating experiment.

"We are thinking about how to jump on the data when Run II starts," CDF's Goshaw said. "We have a new group of physics convenors to set targets and goals. We've set summer 2002 as our target for reporting first results. The physics will be unique."

For either detector, Weerts pointed out, it will take a few months of operating before the real results begin to emerge. Nevertheless, said Weerts, he and his DZero collaborators are already excited about the physics just ahead.

"It's the only reason I am putting myself through this," Weerts said of his role as project manager of DZero's upgrade. "I clearly see the physics in the machine. There are easier ways to make a living than being a detector project manager. But I'm curious. I'd like to see some answers."

Fa la la la, la la la ! |

| last modified 12/15/2000 email Fermilab |

FRLsDFx9eyfrPXgV

Indeed, Weerts said, on a single memorable day in late November, DZero put in place both the heaviest piece of the detector, the 150-ton muon truss, and the most expensive piece, the SVX silicon detector, which cost $7.9 million and weighs a mere 22.4 pounds.

Indeed, Weerts said, on a single memorable day in late November, DZero put in place both the heaviest piece of the detector, the 150-ton muon truss, and the most expensive piece, the SVX silicon detector, which cost $7.9 million and weighs a mere 22.4 pounds.