|

|

!Hecho en Mexico! by Gary Ruderman

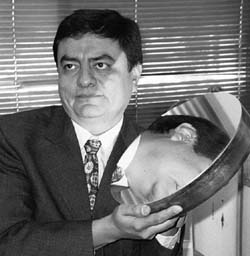

In his 28 years at Fermilab, physicist Herman

White has both witnessed and helped encourage

the globalization of science.

“The focus today is on international cooperation,”

White said, “especially in high-energy physics.

We are a world society.”

With this extended focus, every part of the world

takes on increasing importance—and offers

increasing opportunities.

White recently worked as both kaon researcher and diplomat in helping

complete an agreement with Universidad Autonoma de San Luis Potosi

(UASLP), in Central Mexico north of Mexico City, to build part of the detector

for Fermilab’s Charged Kaons at the Main Injector (CKM) experiment.

While Mexican researchers have a longstanding presence at Fermilab,

the agreement marks the first time that a Mexican institution has been

responsible for building part of a new experiment.

“This is an embryonic collaboration between the U.S., Mexico and Russia,”

White explained. “It’s an opportunity to bring people together from all around

the world.”

The choice of UASLP grew from already-established collegial associations.

This international outreach centers around two Fermilab high-energy alumni:

Jürgen Engelfried and Antonio Morelos Pineda. Engelfried was a postdoctoral

candidate from the University of Heidelberg studying charmed particles at

Fermilab. Engelfried went on to CERN and then to the university in San Luis

Potosi. Morelos Pineda was a graduate student at Fermilab from San Luis

Potosi who studied under the Mexican theorist Augusto Garcia.

Engelfried and Morelos Pineda are also collaborators on the SELEX

experiment, which has announced indications of baryons containing

two charm quarks, a combination never seen before experimentally

(see the story on Page 2).

“The commitment of the scientists really drives many choices for specific

contributions to the project,” White explained. “This is mostly the case for

San Luis Potosi in that our collaborators there have the expertise for

significantly contributing to the design of the detector, including producing

the mirrors. It’s the usual practice to go to those with a history of expertise,

someone you know.”

Fermilab has a history of outreach toward Mexico and other countries in Latin

America, sparked by director emeritus and Nobel laureate Leon Lederman.

While serving as Fermilab director in the late 1970s Lederman called for

more cooperation with Latin America.

U.S. Rep. Rush Holt (D-NJ), former assistant

director of Princeton Plasma Physics Laboratory,

is a proponent of scientific collaboration beyond

the usual connections with Japan and Europe.

He applauded the Fermilab accord with San Luis

Potosi.

“When you consider that much of scientific

research is for the sake of knowledge, in other

words for cultural reasons,” said Holt, “it’s almost

incumbent on the American researchers to include

…some international breadth to the research.”

Holt added that while the United Nations leads

a great deal of the international scientific

collaboration, much more of the cooperation

happens “through some collegial or individual

contacts.”

At Fermilab, connections with developing nations

are growing.

“Now we’re focusing on countries like Bangladesh

and Vietnam, where physicists are in short supply,”

explained physicist Peter Cooper, who signed the

accord with San Luis Potosi as CKM spokesperson.

“We are the United Nations of physics.”

Under the memorandum of understanding, San

Luis Potosi will design and build the mirror array

for the Ring Imaging Cerenkov counter of CKM.

Cerenkov light is produced by particles traveling

faster than the speed of light in water. The light is

focused by a mirror array into the Ring Imaging

Cerenkov counter. Measuring the angle of the

light’s emissions in a cone around its trajectory

allows researchers to measure the particle’s

velocity, trajectory and energy.

The CKM experiment—which hopes to begin

taking data in about 2006—looks at rare kaon

decays that, at their foundation, provide another

view of the properties of symmetry or asymmetry

between particles and antiparticles. The CKM

experiment is designed to maximize the efficiency

of observing and measuring very rare kaon decays.

In the case of kaon decays, rare means quite rare,

indeed. The first measurement of this particular

rare kaon decay required a 15-year search at

Brookhaven National Laboratory. The second was

made in 2001. The CKM experiment at Fermilab

anticipates measuring 100 events in a two-year

period, which White explained would provide a

precise measurement of the decays and another

test of the Standard Model of fundamental particles

and forces.

“Possibly, from a university perspective,” White

said, “participating in a large international research

project will attract students to a unique technical

area, and supporting that participation is just a

good idea.”

Which could, in turn, spur further funding from the

Mexican university. Adding perspective to the San

Luis Potosi collaboration, White said the scientists

who come through Fermilab from other countries

are the “seed corn” for future experiments—and

for future connections.

“Since our motivation is academic,” White said,

“we’ve reached out ever since this facility was built.

As a society, reaching out is what we must do.”

http://www.uaslp.mx

|

“With a GDP of hundreds of billions of dollars there

is no logical reason why Latin America could not

develop to the equal of Europe,” Lederman said

recently. “So why not give them a hand?”

“With a GDP of hundreds of billions of dollars there

is no logical reason why Latin America could not

develop to the equal of Europe,” Lederman said

recently. “So why not give them a hand?” The agreement between Fermilab and UASLP

might also extend its reach beyond the production

of the mirror array.

The agreement between Fermilab and UASLP

might also extend its reach beyond the production

of the mirror array.