|

|

Changing of the Guard

Montgomery succeeds Shaevitz as Associate Director for Research by Mike Perricone

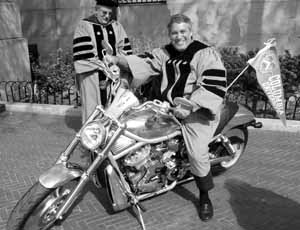

The silver Harley, however, is only

symbolic of his expected time on

the road.

“Jeff Bleustein, the C.E.O. of Harley-

Davidson, gave the commencement

address when my son, Dan, graduated

from the Columbia school of engineering

last month,” Shaevitz said. “Bleustein

arrived on campus riding this new custom

model. I got a photo op.”

The charges of the last three years during Shaevitz’s watch have gone well

beyond the ceremonial. Collider Run II of the Tevatron had its official start in

March, 2001; MiniBooNE is anticipating its first neutrino events; the Main

Injector Neutrino Oscillation Search (MINOS) is progressing both at Fermilab

and at the remote detector site in Soudan, Minnesota; the lab is moving

ahead on a new fixed-target program originating at the Main Injector, as well

as following the recommendations of the High-Energy Physics Advisory Panel

in investigating the possibility of a linear collider. The list goes on from there.

“I feel I owe the lab a lot for my career in physics, and I’m glad I’ve been able

to help in this way for these last three years,” Shaevitz said. “It’s been good

to give something back in the way of service to the lab. I feel that we’ve

accomplished a lot, though of course you always hope to accomplish more.”

Responding to the tiger team report was a

milestone of teamwork under pressure.

“The tiger team examined the entire operation of

the lab,” Montgomery recalled. “They presented an

ocean of findings. The lab had to provide a plan to

respond to those findings. Our response team had

to formulate what the lab needed to do for each

finding, and estimate the cost of doing it. I was

working with very good people—Gerry Bellendir,

Kevin Cahill, Tom Nicol, Rich Stanek, Dan Wolf.

By now these are some of the most senior

engineers in the lab. We completed the report on

time, though everyone had been skeptical about

the target date at first. The consultants who were

working with us called these guys ‘the dream

team.’”

Yet another team-building exercise lay ahead,

on a somewhat different scale. Montgomery was

co-spokesperson of the DZero collaboration, with

Paul Grannis, when the top quark announcements

were made for evidence of a finding in 1994, and

for the observation in 1995. The significance of

the discovery was complicated by the sheer

numbers of collaborating scientists, and by the

communication and review effort needed to bring

nearly 500 voices into accord.

“It was quite challenging and rewarding,”

Montgomery said. “The time scales for a reaction

were not long, given nearly 500 people were all

required to say ‘yes’ before we could make a

move. It was quite a trick, the last few weeks.”

Grannis and Montgomery assembled a review

board of scientists who were not working on top

quark analysis, chaired by Michigan State’s Harry

Weerts, who went on to succeed Grannis as DZero

co-spokesperson.

“Email had matured by then,” Montgomery said,

“so we made strong use of email communications

to tell people what we were doing, what stage we

had reached, and inviting them to contribute and

comment. The collaboration stretched from Europe

to Hawaii.”

For the 1995 discovery announcement, Grannis

gave the talk at Fermilab and Montgomery gave

the presentation at CERN, where he had worked

before moving to Fermilab.

“It was gratifying,” he admitted, “to go back to the

lab you had left ten years earlier, and say, ‘Hey,

we found the top.’”

Montgomery retains British citizenship, along with

much of his North Country accent. His origins are

in Middleham, a village in the cheese-producing

region of northern England. The village grew from

a castle built around the 12th century, which is still

standing. Montgomery described the environs as

“six hundred people, six hundred horses, one

castle, two chapels, one church, and four pubs.”

His interest in physics grew from helping his

instructor assemble lab equipment in secondary

school (his starting class numbered 11 girls and

five boys). He studied at the University of

Manchester (“…and I support Manchester United,”

he added quickly, staunchly establishing his soccer

loyalties). At CERN, he was spokesman for the

European Muon Collaboration before moving to

Fermilab in 1983.

Fermilab is a major participant in LHC, building

components for the accelerator and major

structures of the Compact Muon Solenoid,

and Montgomery saw a challenge ahead in a

new experience for Fermilab physicists.

“We don’t have a great deal of experience with

large numbers of Fermilab scientists working

outside Fermilab,” he said. “But we’ll have our

scientists working remotely at CERN, while we also

serve as a host hub for analysis, for computing,

maybe even for physics here in the U.S.”

But Collider Run II of the Tevatron is the research

priority.

“Fermilab has a very big physics program, and

with its collider and neutrino experiments, one

can argue that it’s the strongest in the world,”

Montgomery said. “We have the highest-energy

machine in the world until the LHC. It’s our duty to

exploit that capability. It’s also tremendously

exciting. The physics potential is very high. We

must execute well and exploit what we have, with

very much a feet-on-the-ground approach. It will

not require a 20-year vision, but it will require

careful nurturing to maximize the results, given the

limited resources felt by all the labs. Maintaining

the right balance, looking for the right opportunity,

and enjoying the ride—that’s no mean feat.

Looking to make the maximum of the opportunity—

that will be my goal.”

Shaevitz will be an active and enthusiastic

participant, teaching at Columbia and continuing

his neutrino research.

“I’m happy Mont decided to take up the reins,” Shaevitz said. “He’s a good choice with a lot of

experience at the lab. And it looks like Fermilab will be the center of the universe

for the next ten years. It looks like most of the important physics in our field

will come out of here. The Tevatron collider has such enormous potential in both discovery and

measurement. The lab will also be the center of neutrino physics. It seems like a particularly good

situation, and it was nice to be able to work on making it happen.”

Nevis Laboratories

University of Manchester

Manchester United

Harley-Davidson

|

A

fter three years as Fermilab’s first

associate director for research, Mike

Shaevitz is ready to saddle up and head

back to Columbia University and Nevis

Laboratories. Shaevitz, a Fermilab

researcher since 1975, will move back

to Westchester, New York in August,

but he’ll make frequent return visits as

a collaborator on the MiniBooNE

neutrino experiment.

A

fter three years as Fermilab’s first

associate director for research, Mike

Shaevitz is ready to saddle up and head

back to Columbia University and Nevis

Laboratories. Shaevitz, a Fermilab

researcher since 1975, will move back

to Westchester, New York in August,

but he’ll make frequent return visits as

a collaborator on the MiniBooNE

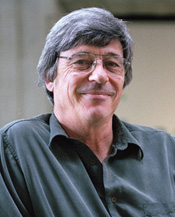

neutrino experiment. The position of Associate Director for Research was created in 1999 by

new Fermilab Director Michael Witherell, with Shaevitz the first appointee.

Fermilab physicist Hugh Montgomery has been named to succeed Shaevitz.

Montgomery moves to the second floor of Wilson Hall bringing two decades

of lab experience, including roles in fixed target experiments, in the “old”

Research Division, the upgrades to DZero, terms as both co-spokesperson

and department head at DZero, and as head of the lab’s response to the

severe recommendations of the 1992 review by the Department of Energy

“tiger team.”

The position of Associate Director for Research was created in 1999 by

new Fermilab Director Michael Witherell, with Shaevitz the first appointee.

Fermilab physicist Hugh Montgomery has been named to succeed Shaevitz.

Montgomery moves to the second floor of Wilson Hall bringing two decades

of lab experience, including roles in fixed target experiments, in the “old”

Research Division, the upgrades to DZero, terms as both co-spokesperson

and department head at DZero, and as head of the lab’s response to the

severe recommendations of the 1992 review by the Department of Energy

“tiger team.” Montgomery (universally called “Mont”) also

organized the 2001 series of “Line Drive” lectures,

highlighting issues involved with a linear collider

as the possible next “big machine” for high-energy

physics after the inauguration of the Large Hadron

Collider at CERN later this decade. He said he

is encouraged by the increased interest and

enthusiasm for a linear collider evident in the

last year, with university groups willing to

participate in research and development for

the machine, as well as in its experiments.

Montgomery (universally called “Mont”) also

organized the 2001 series of “Line Drive” lectures,

highlighting issues involved with a linear collider

as the possible next “big machine” for high-energy

physics after the inauguration of the Large Hadron

Collider at CERN later this decade. He said he

is encouraged by the increased interest and

enthusiasm for a linear collider evident in the

last year, with university groups willing to

participate in research and development for

the machine, as well as in its experiments.