|

|

Historic Turns in The Windmill City by Elizabeth Clements

When the U.S. Atomic Energy Commission selected the former farming village of Weston, Illinois as the site of its planned new national accelerator laboratory, the official address of the new lab was identified as Batavia, Illinois. “The day that Fermilab [then the National Accelerator Laboratory] was announced is probably one of the most historic days for Batavia in the last century,” said Batavia mayor Jeff Schielke. “Without Fermilab, Batavia would be very different today. The Fermilab site would have become another subdivision, and instead of being a city of 25,000 we would be a city of 50,000. Now we have this 6,800 acres of open space that we can enjoy.” The city’s official nickname was soon changed from “The Windmill City” to “The City of Energy,” honoring the lab’s presence on the frontier of high-energy physics. In 1983, the city adopted a new logo that juxtaposes the Fermilab high-rise against a windmill, a symbolic link to its 19th-century heritage. “The City of Energy is proud to have the high-rise as part of the logo, because [Fermilab] has such a positive impact on our community,” said Schielke. Schielke believes the description “City of Energy” also applies to the people of the community. Batavia’s Riverwalk, created largely through volunteer effort, is considered the jewel of the Batavia Park District. The Riverwalk is a 12-acre peninsula on the Fox River that features a display of restored Batavia windmills.

As recently ten years ago, Batavia’s windmill heritage was not highly visible in the city until Robert Popeck, Batavia’s Administrative Assistant to the City, started the Windmill Restoration Project. The project, with the goal of locating and restoring one of each working windmill model that Batavia manufactured, currently has eight windmills on display, two in storage and many future windmill restoration plans. All of the windmills still have the ability to turn, and one of them can still pump water. As a collector of Batavia history, Popeck had always been interested in local windmills. After hearing the historian T. Lindsay Baker lecture about windmills, Popeck approached him and inquired about locating and restoring old Batavia windmills. Baker provided Popeck with a list of contacts, and the Windmill Restoration Project was under way. In the past several years, Popeck has established a network of windmillers and has traveled the country to collect Batavia windmills. “Windmills are a very neat part of Batavia’s history. No other city can claim to have it,” said Popeck. “Windmills are just simple and pretty machines.” Popeck, who has a twelve-foot Batavia windmill in his front yard, receives at least one call a month from somebody who is looking for a windmill. “I have received many positive comments about the display. I like to share my knowledge as much as I can with other people,” said Popeck. “I know just enough to be dangerous.” Some historians credit the American windmill as one of the two inventions enabling the development of the American West (the other is barbed wire). Batavia can thus be credited with playing a major role in the western expansion that occurred following the American Civil War (1861-1865). Founded in 1833 in the valley of the Fox River, Batavia, originally named “Head of Big Woods,” was destined to be a city of industry and progress. The Fox River was the most valuable amenity to the early settlers because it was a source of power for the first Batavia businesses. The area also offered many natural resources for a variety of industries such as timber for the Newton Wagon Company, limestone for at least ten quarries, and rich soil for farmers. The windmill industry, however, is what put Batavia on the map.

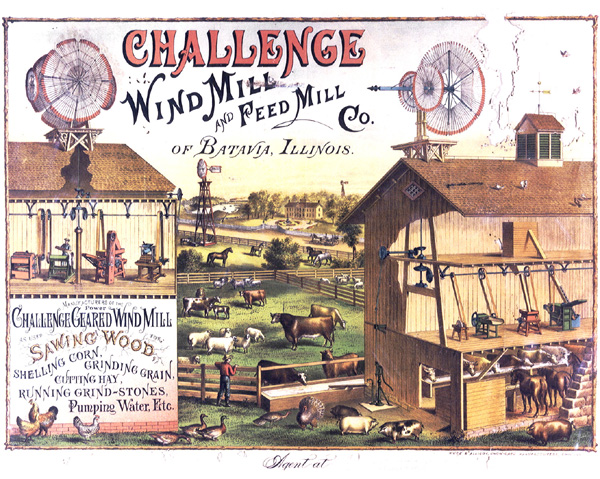

In 1854, Daniel Halladay invented the first American windmill and founded the Halladay Windmill Company in Ellington, Connecticut. The primary function of the American windmill was to pump water, as opposed to the European windmill that served mainly as a gristmill. Having little success on the east coast, John Burnham, the company’s general sales agent, relocated to Chicago to be closer to the windmill market. In 1857, after meeting some businessmen from Batavia, Halladay and Burnham relocated the company and renamed it the U.S. Wind Engine and Pump Company. Within very little time, the company was thriving and produced thousands of windmills that were shipped around the world. Windmill production boomed in Batavia, and in 1867 the Challenge Company was founded, followed by the Appleton Company in 1872. Although Batavia was at one point home to six windmill companies, the U.S. Wind Engine and Pump Company, the Challenge Company and the Appleton Company were the biggest and most famous windmill manufacturers of their time. By the 1890’s Batavia was known as the windmill capital of the world and was nicknamed “The Windmill City.” The windmill industry flourished until electricity and electric pumps became more widely available in the 1930s. The major decline for the windmill occurred during World War II, when metal was needed for the war effort and windmills were not a priority. It took a while for Batavia history to take a turn for the better. On November 21, 1967, President Lyndon B. Johnson signed the bill commissioning the National Accelerator Laboratory (later renamed Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory in honor of Enrico Fermi), and Batavia was back on the map. What was once frontier for the American west became the wider frontier for high-energy physics. And although a windmill serves a very different purpose from that of an accelerator, both share the common threads of technology, progress and, of course, energy. After Batavia became the home of the most powerful particle accelerator in the world, the city’s nickname changed from “The Windmill City” to “The City of Energy.” From the windmill to the accelerator, Batavia has grown accustomed to being at the frontier for modern technology — and might history repeat itself with windmills adapted as generators, in efforts to tap alternative energy sources? The U.S. Department of Energy, for example, has its own Wind Energy Program, which helps utilities understand the benefits and challenges of using wind power by giving them the opportunity to operate wind power plants. And Popeck teaches local elementary and high school classes about the potentials of wind energy.

“Windfarms are popping up in Illinois, Iowa and Wisconsin, and there’s one developing in Colorado,” he said. “The wind generators have a span of 180 to 210 feet. I saw a huge windfarm in California devoted to energy production— it was a spectacular sight to see.”

ON THE WEB:

|