|

|

Breaking The Bottleneck by Mike Perricone

In transmitting their data between America and Europe by network over the ocean, scientists in multinational collaborations find the available bandwidths are significantly narrower and slower than over land, where computer communications systems are highly developed.

"Bandwidths across the ocean are a bottleneck, and they will probably remain a bottleneck for some time," said Fermilab Computing Division Head Matthias Kasemann.

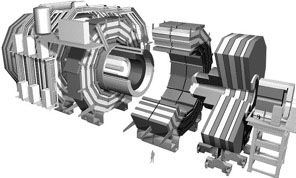

Until a permanent project manager is hired, Kasemann is heading up a project to establish a data sharing system between Fermilab and CERN, the European Particle Physics Laboratory, for the U.S. collaboration of the Compact Muon Solenoid detector. Fermilab will become a Regional Center for storing and distributing data when the CMS experiment begins generating physics results from CERN's Large Hadron Collider.

Kasemann estimated that the overseas bandwidths would have to be enlarged by a factor of 100 to handle the huge amounts of data generated by the CMS and ATLAS experiments at CERN. Until that expansion, the most likely method of transfer would involve recording data on tapes at CERN and flying them to Fermilab for storage in a tape robot system. Fermilab would then transmit the data electronically to the member institutions and scientists of US/CMS.

The project has received initial approval and some funding from the Department of Energy and the National Science Foundation. Fermilab, the host laboratory for the U.S. collaboration building subassemblies of the CMS detector, would also become the collaboration's host laboratory for software, analysis and computing support. As host, Fermilab will have a continually updated copy of all the data used for analysis at CERN, and make it available to all scientists at all universities and laboratories in the U.S. collaboration of 35 institutions in 19 states.

"Now we're really entering into a long-term relationship between the collaboration, the Laboratory and the funding agencies," said Fermilab's Dan Green, Project Manager for US/CMS. "You can build a detector, but the ultimate aim is to do physics with that detector."

Because the scale of the computing needs for the LHC experiments seemed to exceed its capabilities, CERN initiated a project called MONARC--an acronym for Models of Networked Analysis at Regional Centers. Under the MONARC model, each major collaborating country will set up what is called a Tier 1 regional center for data storage and analysis, and for support of the collaboration members. Brookhaven National Laboratory on Long Island, New York, is the host for the US collaboration on Atlas. Other regional centers will be set up in France, Italy, England and Japan for one or both of the experiments, and discussions are underway for a possible regional center in Germany. The concept of the regional center grew from the goal of having data and analysis tools close to the scientists who need it.

"This takes us all the way from soup to nuts," Green continued. "In the past, you'd typically have to be where an experiment is running to do any competitive analysis. The goal is for U.S. physicists to do physics at home, and not have to live at CERN, not have to keep flying there. This is important to the overall success of the experiment."

Fermilab's experience in providing computing support to large collaborations made it a natural choice as the computing hub for US/CMS. Both of Fermilab's detector experiments, CDF and DZero, have between 400 and 500 collaborators, similar in scale to US/CMS. Fermilab is also well practiced in analyzing proton collisions, and the resources of the Feynman Computing Center give Fermilab the most extensive computing infrastructure within US/CMS.

The challenge of what is called "distributed computing," however, extends into realms beyond the technical tasks of making computing data and tools timely and useful for a large number of far- flung scientists. As a computing hub, Fermilab will be storing all data generated from CERN, providing all scientists with the opportunity to work with all the results. Physics data easily and necessarily crosses national borders, offering a potential conflict with efforts in the U.S. aimed at restricting access by foreign scientists to U.S. computers.

Kasemann emphasized that only multinational collaborations can build the experiments and analyze the seas of data they generate.

"These are world experiments," Green added. "In order to do them, you have to use the resources of all the countries involved."

|

| last modified 10/1/1999 email Fermilab |

FRLsDFx9eyfrPXgV

The Atlantic Ocean effectively separated Europe and the Americas until the end of the 15th Century and the great age of exploration, and it still poses problems in this age of the Internet.

The Atlantic Ocean effectively separated Europe and the Americas until the end of the 15th Century and the great age of exploration, and it still poses problems in this age of the Internet.

Setting up as a regional center will require about $10 million in computer equipment, equivalent to that used in each of the CDF and DZero upgrades for Run II. DOE and NSF started funding for the hiring of computing professionals for the project, and Kasemann estimates 30 to 35 people will eventually work on the computing effort, with many drawn from current Fermilab resources as Tevatron Run II preparations are completed. The software and support have to be ready to go on the first day CMS is running, and the experiment's lifetime is projected at 15 to 20 years.

Setting up as a regional center will require about $10 million in computer equipment, equivalent to that used in each of the CDF and DZero upgrades for Run II. DOE and NSF started funding for the hiring of computing professionals for the project, and Kasemann estimates 30 to 35 people will eventually work on the computing effort, with many drawn from current Fermilab resources as Tevatron Run II preparations are completed. The software and support have to be ready to go on the first day CMS is running, and the experiment's lifetime is projected at 15 to 20 years.

"It is always the understanding in every international collaboration that every scientist has access to all the potential physics data of an experiment," said Kasemann, who is from Germany. "This is a very sensitive point in how high energy physics works, and how we work together. It's completely impossible to limit access, and say that certain nationalities or certain members cannot have access to data. That makes the whole idea of working together in collaborations like CMS, CDF and DZero impossible."

"It is always the understanding in every international collaboration that every scientist has access to all the potential physics data of an experiment," said Kasemann, who is from Germany. "This is a very sensitive point in how high energy physics works, and how we work together. It's completely impossible to limit access, and say that certain nationalities or certain members cannot have access to data. That makes the whole idea of working together in collaborations like CMS, CDF and DZero impossible."